Hands-on data storing

- Folder structure

- meta data

- Data provenance

Note: most of the text on these pages are for future reference for you and colleagues. We will discuss the information live in this workshop. You can find the exercises in the menu left, or by finding the blue blocks on the page.

Introducing Reproducible Research

Reproducible research means that you work in a way that makes it possible for someone else to reach the same results from your data. Within ONTOX, this is an important concept, as reproducibility leads to increased rigour and quality of scientific outputs, and thus to greater trust in our results.Additionally, a reproducible workflow leads to a decrease in headaches over your own project data management, revisions, and using data or analyses from previous projects.

In general, the most important part of a reproducible workflow around a dataset is giving all meta data on your data (including your hypotheses, study design, specifics on your data collection and all the analysis steps you took, as well as any publications based on this data.) The second most important thing is version control: keeping track of any changes to your dataset, and to any documentation accompanying it. We will start with setting up a folder structure to store this information.

What you need for replication

To replicate a scientific study you would need some information from and information about it. So this is the information that we should be keeping together when working on a project:

- Context and interpretation Scientific context! Research questions, related publications..

- manuscrips

- presentations

- posters

- Methods Exactly how the data was gathered

- protocols

- code from experiments

- ethical committee approvals

- Data

- the raw data itself

- meta data (which is data about the data. For instance who gathered it, when, where, licence information, keywords…)

- Data analysis All steps in data analysis

- Exploratory data analysis of the data

- data mangling decisisons, such as fitering and outlier selection

- processed data

- Which inductive statistical tests or inference was done and how.

Guerilla analytics folder structure

I you set up your projects in a way that makes it easy to find all this information, you will save yourself and others a lot of time. To help you start building this we will use the Guerrilla Analytics framework, as described by Enda Ridge in this booklet.

Some key Guerrilla Analytics Principles to remember:

- Space is cheap, confusion is expensive

- Use simple, visual project structures and conventions

- Keep an intact link to data and the dissemination of knowledge (e.g. papers based on the data, emails)

- Version control changes to data and analytics code

- Consolidate team knowledge (agree on guidelines and stick to it as a team)

Guerrilla Analytics book by Enda Ridge,

non reproducible folder structure

A quite common way to organise our digital files, is by making categories. For instance, both of your teachers today organised their laptops previously similar to:

old_laptop/wrong_structure

├── courses

├── ethical approval

├── failed projects

├── images

├── manuscripts

│ ├── me_et al , 2020_v01 - Copy.docx

│ ├── me_et al , 2020_v02.docx

│ └── me_et al about A, 2020_v03_final_final.docx

├── presentations

├── project A

│ ├── Data files 001

│ ├── Project Documentation

│ ├── Volunteer responses

│ ├── analyses

│ └── revision

│ ├── new analyses

│ ├── new figs

│ └── replies to reviewers

└── protocols

This makes sense but has at least two major drawbacks:

- Deep nesting of files in folders can cause you to lose files, or the link between files. Most importantly, in 10 years time: will you remember on what dataset a specific powerpoint presentation was based? It is essential for reproducible research that the link between data and analyses and interpretation remains intact.

- Things will change. There will be new categories and new types of files, you had not thought of before. Where will these go?

reproducible folder structure

So when managing files in projects adhere to the following guidelines

- Create a separate folder for each analytics project . Keep the unit of a project small.

- Use the same folder structure in every project Better even: agree on a folder structure as group.

- Do not deeply nest folders (max 2-3 levels, so no project/documentation/applications/metc/first_communication/input/docs/moredocs/mail.txt)

- Keep information about the data, close to the data. Save a README.txt in the data folder with for example descriptions about variables and meta data.

- Store each dataset in its own sub-folder. example below.

- Do not change file names or move them. Don’t change a file name of a file you recieve or download from the internet. If you absolutely have to, record your changes in the README.txt file.

- Do not manually edit data source files. if you can prevent it. You can (almost) always solve this using code. If you absolutely have to, record your changes in the README.txt file.

- In code, use relative paths (so not mylaptop/users/alyanne/studyA/data/etc) as absolute paths will change over time.

So for instance, your folder structure could look like this:

new_laptop/better_example_structure

├── courses

├── project A

│ ├── analyses

│ │ ├── code

│ │ ├── data

│ │ └── data_raw

│ │ └── Volunteer responses

│ ├── documentation

│ ├── ethical approval

│ ├── images

│ ├── manuscript

│ │ ├── me_et al , 2020.docx

│ │ ├── version 1

│ │ └── version 2

│ ├── methods

│ │ └── protocols

│ └── presentations

├── project B

└── project CExercise A1: cleaning your own folder structure

15 minutes

Look at your research projects. Which example folder structure does it resemble the most?

- What needs to be done to clean your folder structure?

- Try to fix a few things right now.

- Book a timeslot (e.g. 1 morning) in your calendar somewhere this month to fix the folder structure of your current projects.

File names

Well, having neat and tidy folders of course won’t be enough. There is more needed to work reproducibly and save future you a headache when revisiting a project.

One note on file names:

The main trouble with file names is actually not a file name problem, it is a version control problem. You will recognise this:

The use of version control abolishes the need for inventing a file name every time you save it. We will discuss version control in the second half of this workshop. With the use of proper version control you only have to think about naming a file just once with a good name. But what entitles a ‘good’ file name?

A good file name is:

- Unique in a folder (prevent duplicated names)

- Is short, but most importantly : descriptive (if you need it to be longer to be descriptive enough, choose that)

- Does not contain any special characters except for

_and a.before the extension. Special characters are reserved for other purposes and can cause problems when a back-up of the files is made or when files need to be loaded in analyzing software or when copying files. - Be consistent. Important, but also hard!

- Don’t use sequential filenames (e.g. “fig3A.png”, “final_data.csv”) as this will usually change as the project evolves.

- If you receive a file from somebody else: Never change the file name, even if it does not meet the above requirements. Changing a file name causes a breakage between the file and the source it came from. If you change a file name you received from a person or downloaded from the internet, the person who send the file will not know about the new name. Also, you won’t be able to trace it back to the source.

Meta data

Meta data is data about the data, such as for instance the type of variables, number of observations, experimental design and who gathered the data. This is quite often not reliably documented (or at least not easily accessible) but very important: data without context loses some of its purpose.

Take a look at this Wikipedia image of cocoa pods and scroll down. As you can see, Wikipedia stores a lot of metadata on file usage, licence, author, date, source, file size… Even the original meta data from the camera is included (scroll to the bottom).

Meta information for data files, like type of variables, ranges, units, number of observations or subjects in a study, type of analysis or experimental design often goes in a README.txt file or a sheet in the Excel file containing the data. Keep the readme information close to the data file. Also, information about who is the owner of the data or who performed the experiment when and where and with what type of device or reagents is very useful to include.

Over at the The Carpentries Incubator, there is a really nice example of meta data in life sciences:

According to How to FAIR we can distinguish between three main types of metadata:

- Administrative metadata: data about a project or resource that are relevant for managing it;

- E.g. project/resource owner, principal investigator, project collaborators, funder, project period, etc. They are usually assigned to the data, before you collect or create them.

- Descriptive or citation metadata: data about a dataset or resource that allow people to discover and identify it;

- E.g. authors, title, abstract, keywords, persistent identifier, related publications, etc.

- Structural metadata: data about how a dataset or resource came about, but also how it is internally structured.

- E.g. the unit of analysis, collection method, sampling procedure, sample size, categories, variables, etc. Structural metadata have to be gathered by the researchers according to best practice in their research community and will be published together with the data.

Descriptive and structural metadata should be added continuously throughout the project.

Exercise A2: Identifying metadata types

Exercise by FAIR in (biological) practice course on carpentries-incubator. (see below for full reference)

5 minutes

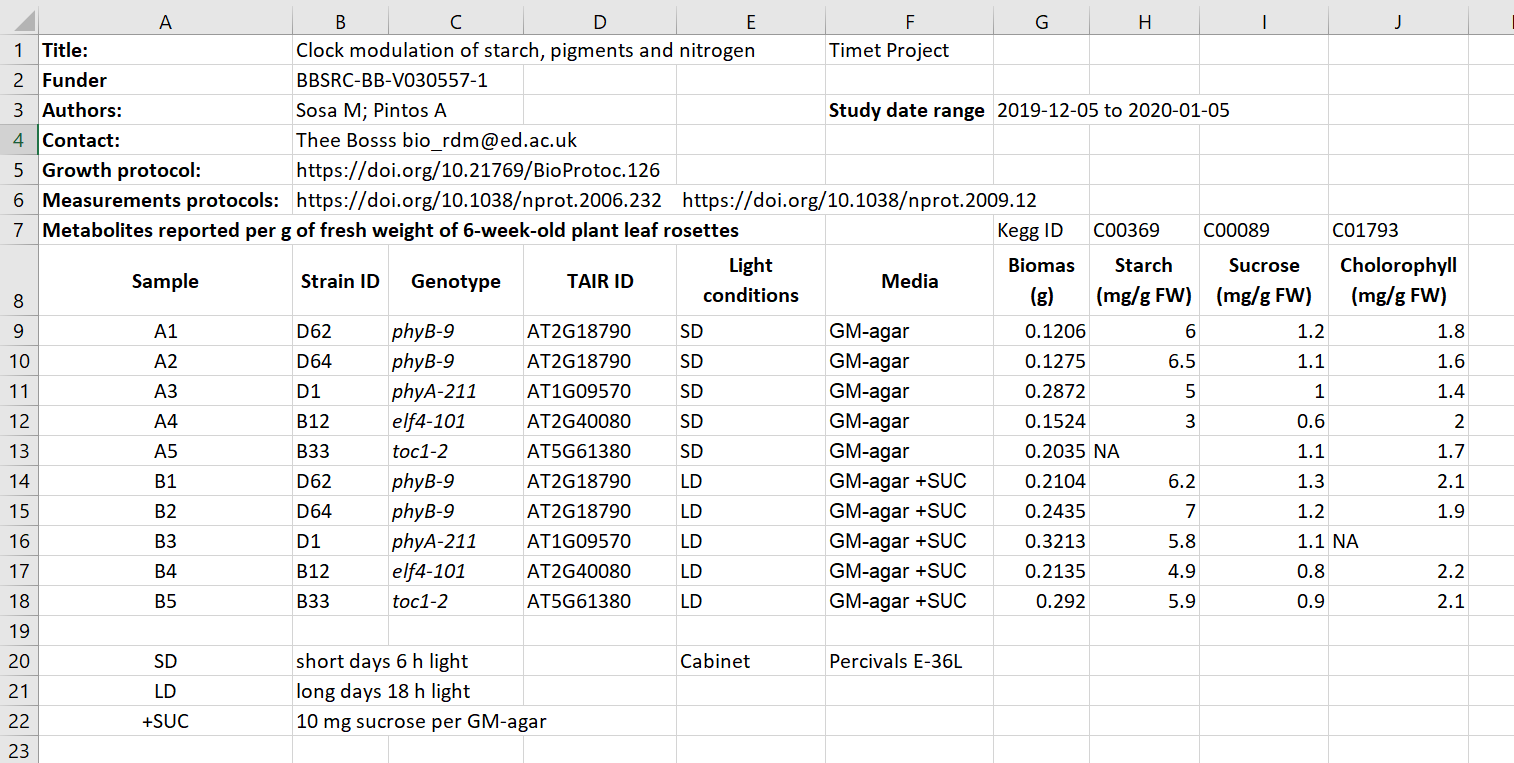

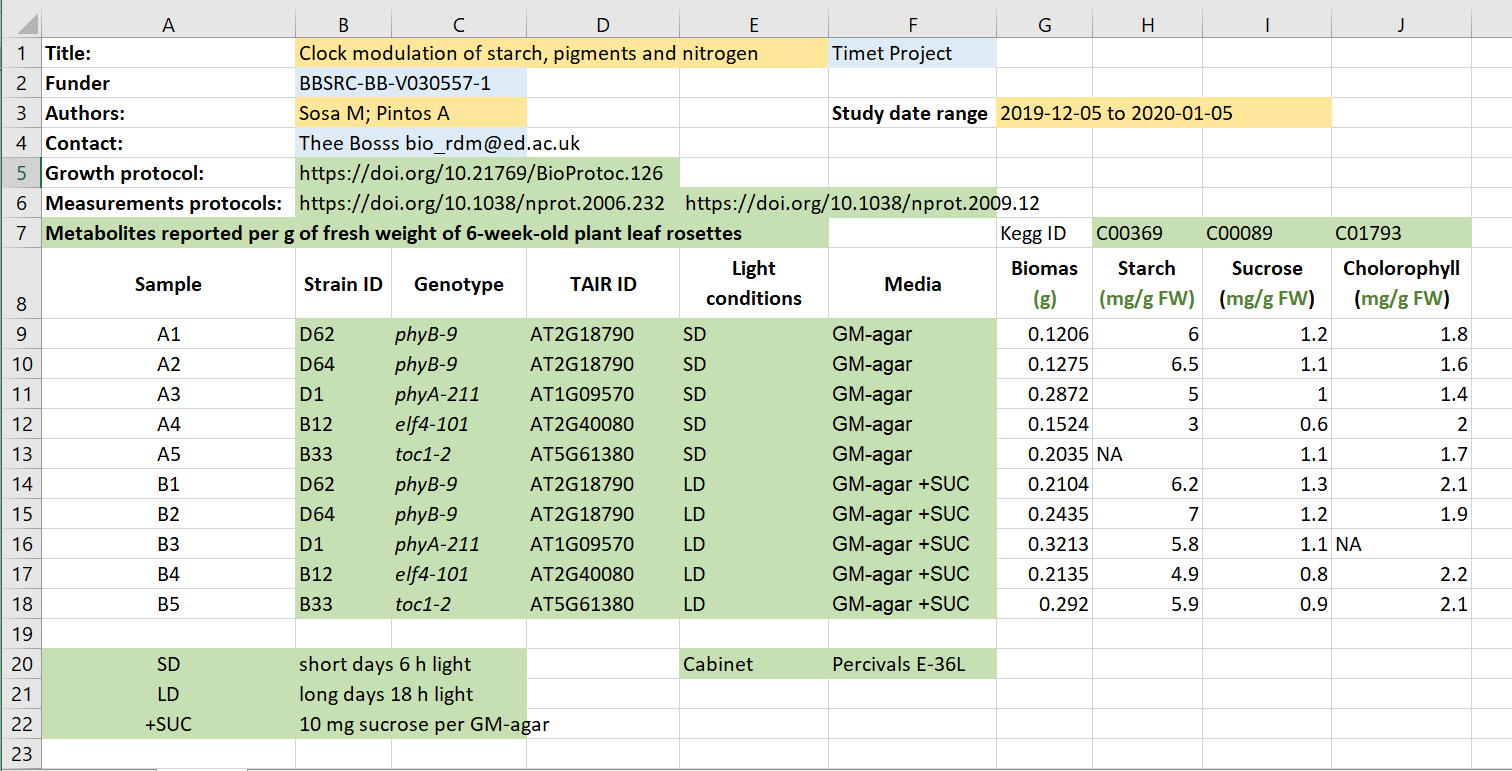

Here we have an excel spreadsheet that contains project metadata for a made-up experiment of plant metabolites:

Figure 1: example of a meta data file

Figure credits: Tomasz Zielinski and Andrés Romanowski

In groups, identify different types of metadata (administrative, descriptive, structural) present in this example.

Click here for a solution

- Administrative metadata marked in blue

- Descriptive metadata marked in orange

- Structural metadata marked in green

Source: FAIR in (biological) practice. Licensed under CC-BY 4.0 2022. We took Exercise 1: Identifying metadata types out of context, but we actually would recommend looking at all their course material when you find the time.

What should be in a meta data file?

Save at the very least in your meta data file (usually called “meta data” or “readme”):

- Administrative metadata:

- title

- information about the authors (name, institution, email address)

- license information

- Descriptive or citation metadata:

- short description

- date the file was created

- date of data collection

- location of data collection

- description of methods (you can link to publications or protocols)

- description of data processing

- any software or specific instruments used

- Describe details that may influence reuse or replication efforts

- Structural metadata:

- variable list (full names and explanations)

- units of measurements

- definition for missing data (NA)

- whether you changed anything in the data file manually (better not to!), if so: when, why and how.

Here is a nice example file by the university of Bath for bioinformatics projects, another more general template available for download, and here another template for experimental data

This may seem to be a bit too much, but try and see how much you could fill in and keep the template for future projects!

Exercise A3: starting to add meta data files

15 minutes

- Google and discuss whether there are meta data standards for your field.

- Start to add meta data files to your current most active project if you don’t have them. If you don’t have an agreed on format, just open a word/excel document and start adding administrative, descriptive and structural meta data. Remember that any metadata is better than none.

Version controlling data & data provenance

Important in a project like ONTOX is data provenance. Provenance describes the the place of origin or earliest known history of something.

Data provenance thus means that for each data point you use, you should be able to tell where it came from. Where was it collected, by whom, which experiment, etc.

Obviously, keeping meta data with your data and not changing raw data file names helps solve the bulk of this problem. There is an issue though: data may change. You may for instance receive an updated dataset. What now?

- Each dataset you receive goes in a numbered folder in the data-raw folder. If you recieve an updated file, you add the old file to a new folder called

v01inside the orginaldatafolder. - The updated file replaces the old (v01) file. If then you recieve yet another update, you can repeat this trick with a

v02folder inside thedatafolder again. - In this way, the file directly in the data folder is always the latest updated version.

- Keep track of the changes in your meta data file.

- always immediately update your meta data file, and keep it together with the data at all times. Losing your meta data is like storing shelves full of unlabeled tins…

key points

- use a project centered folder structure and be consistent

- keep meta data with your data

- don’t change data files, use versioning

- always keep current, used, data in the main /data folder, store older versions in subfolders called

v1,v2etc